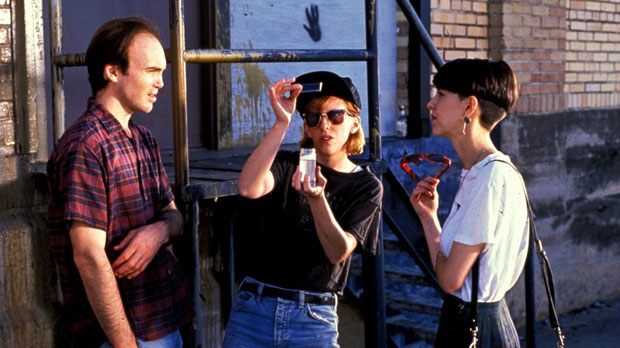

Slacker (1991) Orion Classics/Comedy RT: 100 minutes Rated R (language) Director: Richard Linklater Screenplay: Richard Linklater Cinematography: Lee Daniel Release date: November 1991 (Philadelphia, PA)

Slacker (1991) Orion Classics/Comedy RT: 100 minutes Rated R (language) Director: Richard Linklater Screenplay: Richard Linklater Cinematography: Lee Daniel Release date: November 1991 (Philadelphia, PA)

Rating: *** ½

Not only is Slacker the debut feature of writer-director Richard Linklater, it’s also one of the movies that got the independent film movement rolling. Linklater took all the rules of conventional cinema and threw them out the window with this most unconventional film that’s admittedly not for all tastes. Forget about plot, there isn’t one. The same goes for character development; he never stays with one long enough for that to happen. Structure? Yes, it has that and that’s where Slacker differs greatly from anything you’ve ever seen. It goes like this. A character enters the frame and talks for a few minutes before the camera starts following somebody else, either somebody the character was talking to or a passerby. We follow that person for a few minutes until Linklater shifts the focus to somebody else and so forth. In the end, we meet about 100 different people.

A “slacker” is defined as “a young person who is perceived to be disaffected, apathetic, cynical or lacking ambition”. It’s an apt description of the young (and some not-so-young) people that populate Slacker. Set in the college town of Austin, it takes place over a single 24-hour period. It opens with a young man (played by Linklater himself) exiting the bus station and hopping into a taxi. He proceeds to tell the disinterested driver about a dream he had during his bus ride. He babbles for a few minutes before getting out. Seconds later, a hit-and-run takes place. People gather at the scene while the driver pulls up in front of his house and goes in where he burns some old yearbook photos and puts on an old home movie. The police arrive a few minutes later and take him into custody. A street musician walking past asks somebody what happened and moves on. A woman walks past him performing on her way to a coffee shop where a group of young men are engaged in an intellectual conversation. One of them leaves and is followed by a man who overheard him say that he hadn’t seen an acquaintance in months. The man tells him there’s a conspiracy behind all the people that go missing all the time. This is how the whole movie plays out.

Over the course of Slacker, we also meet an elderly anarchist, a JFK conspiracist, a woman who photographs Dairy Queens, a man who collects TVs and a strange woman (Butthole Surfers’ drummer Teresa Taylor) selling what she claims is a “Madonna pap smear”. We hear bits and snatches of conversation in bars, coffee shops, homes and on the street. My personal favorite is the two guys discussing the sociological meanings behind the Smurfs and Scooby-Doo. These are people who all live inside their own heads.

Slacker is a very funny movie. Instead of written dialogue that’s neither as clever nor witty as the writers who wrote it think it is, Linklater breaks free of these Hollywood shackles and allows us to hear conversations that sound like they’re spoken by real people. Much humor can be found in listening to the conversations of others. It can also be found in people’s eccentricities and idiosyncrasies. By not investing too much time in one character, Linklater imbues Slacker with a sense of spontaneity. Watching it is kind of like taking a walk around Austin and drinking in the local flavor. But you don’t have to go to Texas to meet people like this. I attended university in Pennsylvania in the early 90s and met eccentrics of all kinds. Young people do tend to be disaffected, apathetic and self-involved. Slacker is a very realistic portrait of this particular social stratum. Everything about it feels so real. It has a shambling appeal to it. Granted, the narrative device does wear a bit thin near the end but it never ceases to be entertaining. It’s more than deserving of its cult status. What’s more, it’s a sign of the great things yet to come from Linklater (e.g. Dazed and Confused, the Before trilogy and Boyhood). Wholly original, riotously funny and pointed in its observations, Slacker exemplifies what independent film is really about.

SPECIAL NOTE: Don’t confuse Slacker with the abysmal 2002 teen comedy Slackers. They’re two completely different movies. One is great, the other is Slackers. One redefines cinema, the other exemplifies everything bad about cinema. ‘Nuff said?